Award Worthy

On not winning and the dissolution of the self.

The 2025 Booker Prize shortlist novel, The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny opens with a paragraph that gives weight to Ann Patchett’s cover declaration which crows of “spectacular literary achievement.” A single opening paragraph stuns the reader into splendid submission,

“The sun was still submerged in the wintry murk of dawn when Ba, Dadaji, and their daughter, Mina Foi, wrapping shawls closely about themselves, emerged upon the veranda to sip their tea and decide, through vigorous process of elimination, their meals for the rest of the day. Orders must be given to the cook at breakfast so that he could go directly to market. It was Mina’s fifty-fifth birthday, the first of December in the year 1996, and the mutton for the dinner kebabs had been marinating overnight in the kitchen.”

In a mere 106 words, author Kiran Desai offers up a visual feast of setting, character introduction, and details of a daily routine with just the right amount of atmospheric artistry. And yet, she’s no winner, this time around anyway.

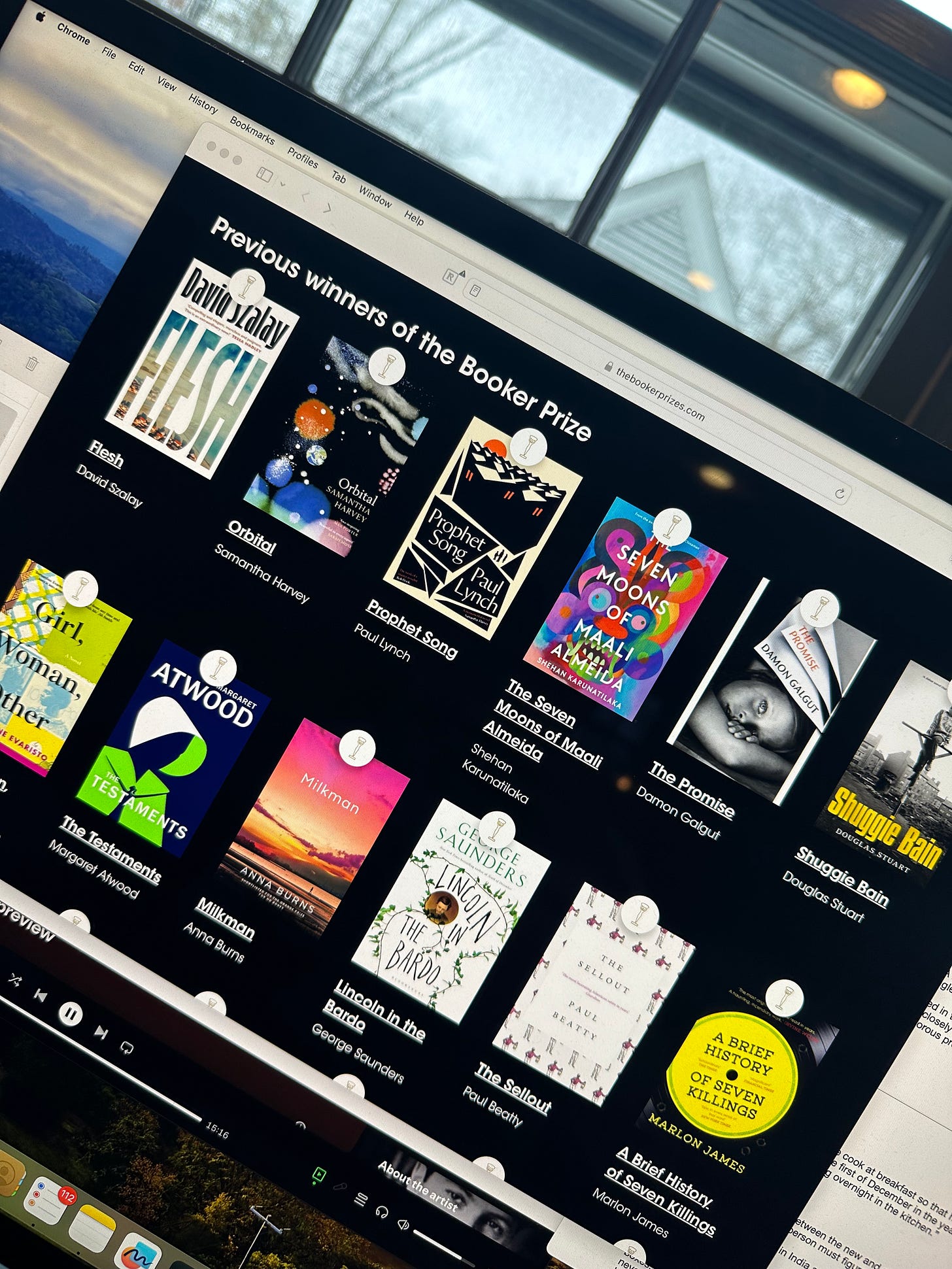

If you are a member of the bookish class, you will, by now, have heard that David Szalay clinched the 2025 Booker Prize for his formidable novel, Flesh. Szalay deserves the award, as do, I am sure, each of the other finalists in the category. See my April review of Flesh here:

One truth all humans are certain of — any awards process is inherently unfair, or, perhaps, more accurately stated, any decision process run by humans is flawed. No matter the rigor of the evaluation matrix, the review will inevitably encompass personal preferences, life experience, and perspectives of a fallible being. It would be foolish to mistake this statement for disillusionment or skepticism over the awards process; all of this is to say, simply, that the best of the best is often one of the best.

That said, as far as literary road maps go, the Booker is often my favorite. They get it right so much of the time. Not a single dud resides on the winner list of the last decade. From the maddeningly complex syntax of Anna Burns’ Milkman, mirroring the maddeningly complex Troubles-era Northern Ireland, to the heartbreakingly resonant Shuggie Bain and all-time favorites Girl, Woman, Other and Orbital, I hold deep admiration for each and every work.

This year’s shortlist was particularly well stacked, consumed in large part with what it means to walk the earth as a flawed mortal, both yearning for and repelled by relationships, familial and otherwise. Each is, in its own way, a study of the self.

Flashlight by Susan Choi (American)

The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny by Kiran Desai (Indian)

Audition by Katie Kitamura (American)

The Rest of Our Lives by Ben Markovits (American)

The Land in Winter by Andrew Miller (British)

Flesh by David Szalay (Hungarian-British)

The struggle with the self saturates our current pop culture moment. In Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere, Jeremy Allen White dissolves into Springsteen, mimicking his singing voice with such seamless alacrity that the viewer would be forgiven for assuming dubbed tracks with The Boss’s voice are responsible for the soundtrack.

An actor inhabiting the character they are paid to play is one thing. An actor inhabiting a well-known musician the public thinks they know, but who privately struggles with an entirely different sense of self, is another thing entirely. The laser focus of Deliver Me From Nowhere gives White the gift of occupying a very specific period of time in The Boss’s life during which Springsteen, wrestling with depression, failed to accept that which others wanted him to do in favor of honoring the story he needed to tell. Out of that refusal to please emerged Nebraska, arguably the most discussed album of his oeuvre.

It would, before moving on, be irresponsible to neglect the presence of a volume of Flannery O’Connor’s work on The (movie) Boss’s coffee table. O’Connor herself was a woman who struggled with ambition, its impact on the self, and the question of ego.

To exist in the current moment of selfies | curated profiles | first looks cast not across a bar but via a screen, raises all manner of questions about what it means to be human. Ancient religions have long wrestled with the absence of the self, meditation (a booming online business itself), too, has since the dawn of time worked to erase any grandiose sense of separation from the larger universe.

On the streaming front, Vince Gilligan’s new love letter to the city of Albuquerque offers up a thought experiment in what it might mean to (mostly) wipe out humanity as we know it, replacing its current violently fractious state with an anodyne population that speaks solely in saccharine verbiage as it navigates a significantly altered world. Pluribus (starring the startlingly expressive Rhea Seehorn) asks a clear question: if we could eradicate conflict, war, racism, poverty, and any other societal weakness along with the individual self, would we/you make that trade?

Back to the review at hand. To read The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny as a straightforward narrative bedazzled with seductively smart prose is a perfectly noble endeavor. That requires, though, an underestimation of Kiran Desai’s immense talent, speaking out, via story, about the isolation long familiar to immigrants living far from home. Loneliness is now classified as an epidemic, blanketing those who fear leaving the comfort of the domestic sphere to say nothing of adventuring abroad.

Sunny and Sonia, both born in India, are visitors each to America. Sunny, a nightshift reporter for the AP, lives in New York City with his Midwest American girlfriend, Ulla. Sonia, a student, starts the book in the snow-covered mountains of Vermont, engaging in a deeply unhealthy but loneliness-alleviating relationship with a troubled artist.

Palpable tension between the new and old world is one thing, rude and unsparing in its insistence that one must forsake their homeland in order to settle comfortably on the other side of the globe. Sunny, on the heels of a breakup, returns to India from his New York City life. He works as an AP journalist but cannot grasp how he might tell the stories of his homeland.

“Sunny broke the silence between himself and Babita by accusing Babita of bringing him up in such a Westernized manner that he’d always be a foreigner in his own country, unable to reach important stories. He’d lost his natural sense of identity to one of T.S. Elliot and cheese sandwiches. Sunny said every other student at school had brought roti and sabzi in their tiffin boxes, watched Bollywood movies on the weekends. He’d barely touched his nation. He’d never taken a bus, never eaten in a Dhaba. It was in the States where, for the first time, he had lunched at street vendor carts, caught public transport, used toilets in bus stations.

“So regain your identity then, who is stopping you?” snapped Babita. “You’re the one who refused to eat almost all Indian food when you were growing up. You would take a jar of peanut butter everywhere! Now learn Hindi properly and hunt down a true story.”

If Sunny could recover the meals of lost years, couldn’t he also recover the stories? “In India,” an envious Norwegian journalist had told him, “stories grow on trees.” But Sunny had no right to them, hundreds of thousands ripening and dropping like fruit before they could be picked. Stories on the confluence of corruption in politics, business, the military; stories about weapons deals, the eviction of Adivasi from their forest homes, AIDS. He might broach these only if he agreed to lose his privilege. To lose his privilege was tied to his mother, and he could not lose his mother—his mother would refuse to lose him, no matter how angry she was.”

To be a valued philosopher requires a constant meditation on identity, its role or absence in the daily life of a human endowed with inalienable rights. To confront this question requires a good deal of hutzpah, time, and, frankly, arrogance that you might have the answers others so steadily ignore.

NYU professor, art critic, media theorist, and philosopher Boris Groys wrestles with this age-old question in Alexandre Kojève: An Intellectual Biography, an excerpt of which was released on Literary Hub earlier this week.

“This universality of human non-identity—which is based on the self-identity of nothingness—is the source of Kojève’s conviction that human history will end with the establishment of a universal and homogeneous state in which everyone’s non-identity is recognized.”

Of course, it is entirely impossible to erase all inherited collective reflection on the ego and simply read Desai’s book for what it is: a highly enjoyable, severely thoughtful, family saga that exudes irresistible charm. Looking for a masterclass in craft? You’ve reached your destination.

Sonia and Sunny are writers; for the lit-obsessed reader, the flotsam of their everyday work is a reading list worthy of an MFA syllabus.

“For the critical part of her thesis, Sonia wrote a treatise on the subject of magic realism as it graded into orientalism […]

Sonia argued that Latin American, Asian, and African cultures possessed a great deal of homegrown magic. Rumors of ghosts came bursting out of folk societies, especially those without electricity. Superstition possessed the richness of art. A fantastic tale was another kind of mirror, another kind of metaphor, a way to expose larger-than-life brutalities, a rot beyond rational understanding, a way to say things about a dictator you could never say outright. Also, there was the practical purpose of being able to leap between times and places, to reveal patterns and connections beyond the reach of a realistic book in realistic time. Sonia referenced Bulgakov and Dinesen, Calvino and Rushdie, Morrison and Márquez.”

There too is food (delicious descriptions of feasts humble and grand alike plus Sonia’s kebab project exploring local rivalries and recipes); perceptive descriptions of differences between Sunny and his Midwest American girlfriend (“Ulla showed Sunny how to snip open cartons, buy fabric softeners and drying sheets, telephone for a gas connection, order a hamburger (how lucky she was to be with a Hindu who ate beef, she had no idea”). Visceral visual details (“gums black from smoking […] forehead and cheeks carpeted with boils) and scenes drenched in candlelight, ketchup, and perhaps the best weather description I’ve ever read,

“Babita and Sunny strove homeward, as if swimming a breaststroke in a pond of hot spinach […]”

If you haven’t yet placed your online library hold or clicked the alink above to have a copy shipped directly to your home, let me leave you with this: Sonia and Sunny's relationship is oneI couldn’t look away from. Kiran Desai has crafted a masterpiece far from the fragmentary, short-fiction trends of the current moment, offering the reader a gorgeously rendered book quite impossible to put down. I am deeply fond of this exceptional work.

Sarah Jessica Parker’s Year of Judging the Booker Prize | Sounds glorious and deeply isolating, a potentially life-changing combination.

Heartland Masala: An Indian Cookbook From An American Kitchen | I am obsessed with the story of how this cookbook — by Darlingside’s AUYON MUKHARJI and his mother, a deeply accomplished home cook — came to be. Listen here for the entire story.

A Domestic Cookbook | Stumbled across the oldest published cookbook by a Black American woman whilst doing a bit of research at Kitchen Arts and Letters yesterday. This important historical cookery book was reissued in a brand-new edition earlier this year. One for the historical foodie fan, it would make an excellent holiday gift.