Book lovers often suffer from self-imposed overwhelm. The number of new titles released each week would make even the sturdiest of tables groan with the weight of material printed. Should one add the millions of words typed into newsletters, online serials, and digital articles such as this one, the table would undoubtedly splinter and split in two.

Recently, I made a personal pact with myself to wade beyond the new and constant stream of bright shiny things passing by, resisting the urge to grab every of-the-moment literary delicacy that comes my way, fast as glistening, glittery nigiri on a sushi conveyor belt. This doesn’t mean I didn’t just place an order for several hardcover-only1 August 2025 releases, but it does mean that a year and a half after stepping away from the independent bookstore industry, I’m allowing myself to pick up a backlist title every now and again.

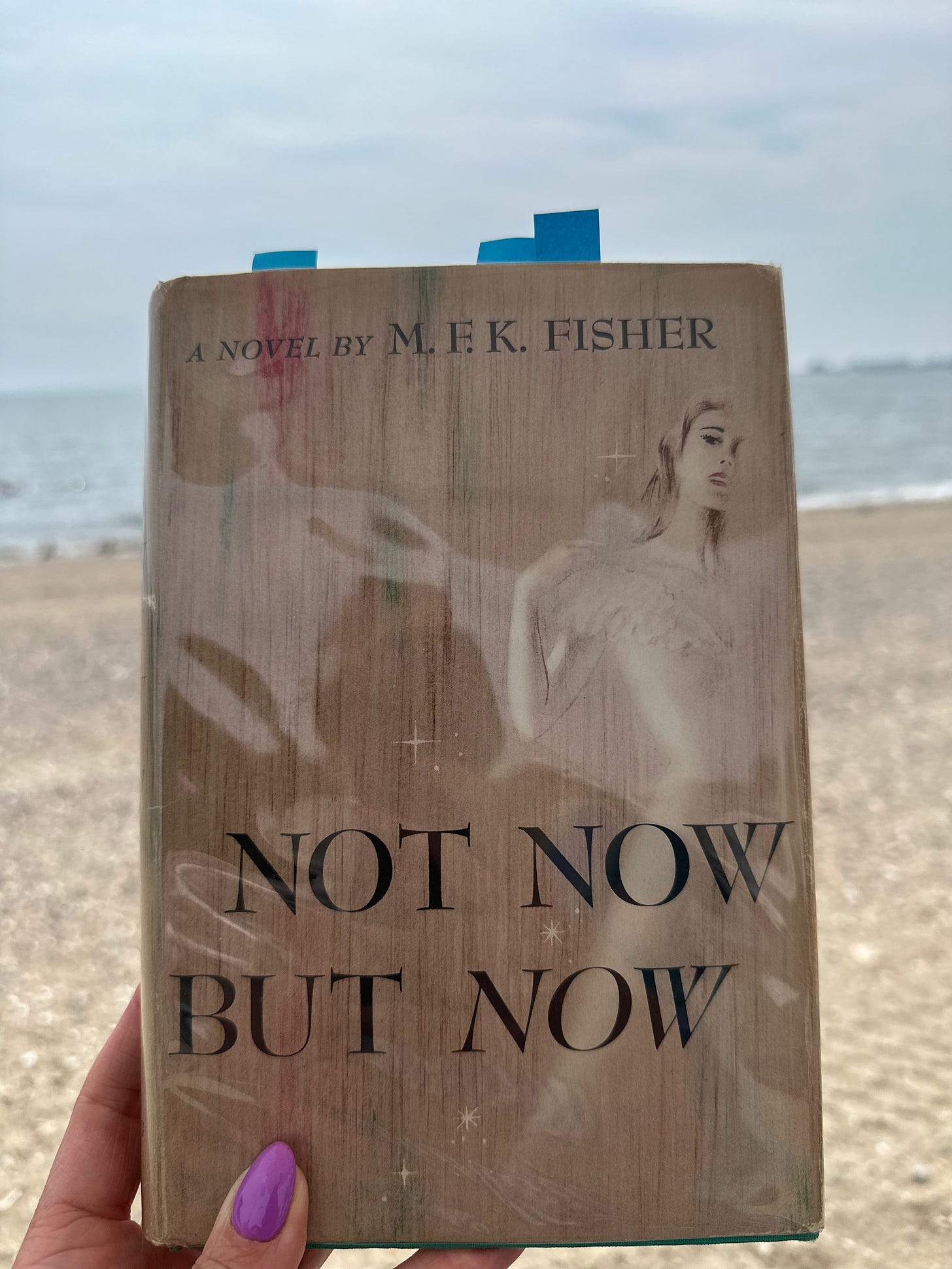

Last month, taking up time and space in the beloved Rabelais, I scooped up a first edition of M.F.K. Fisher’s novel Not Now But Now, along with Joseph Mitchell’s The Bottom of the Harbor and Old Mr. Flood (look out for future book reports on the writer Adam Gopnik this week called “at once the most lucid and the most mysterious of the great mid-century New Yorker writers.”).

Now, before you comment, suggesting that I’ve mindlessly mistyped “novel” in front of the aforementioned title from renowned food writer M.F.K. Fisher, I assure you that I have indeed properly categorized this particular book. Fisher, born and raised in Southern California, penned more than 25 books2 over her prolifically productive lifetime, a single volume of fiction among the stack. She (b. 1908 - d. 1992) used initials in place of her given name, Mary Frances Kennedy, in the hopes that the public might take her seriously and not pass judgment on sex alone.

Why the suspiciously singular leap to fiction, you wonder? Husband number three, Donald Friede. By the time M.F.K. Fisher decided to try her hand at the novel, she was already a well-established culinary writer. At the very end of her life, when all Mary Frances could stomach was a periodic slurp of a briny, creamy oyster, Ruth Reichl arrived at her bedside and asked about that decision:

“We had a good but dumb marriage,” she whispers, “and we always remained friends. But he wanted me to be a novelist; he thought every writer had one good novel in him. But God, no, I’m not a novelist.” She emits what would pass for a laugh in someone who still owned a voice.

To please her publisher husband, she wrote one novel, Not Now but Now. It did not please her—and it did not sell. “Donald had wanted me to be a bestseller, and I was not. In 1954, he decided I was through. So he came up with the idea of reprinting my five first books in one volume.” She gives another one of those quasi-laughs. “He was very pleased. The Art of Eating has never been out of print.”3

Doing something to please a third-rate husband isn’t generally considered a tried and true formula for success. But there exists in my mind a curious wonder: was that all, Mary Frances? Was the play of putting pen to paper, detailing the hard-drinking, emotionally bankrupt Jennie, simply enacted to stop your beloved’s incessant yapping? Or was it in line with your modus operandi, the only suitable response: to just do the thing that no one expected of you and, in the process, shift public perception. As prolific as the summer crop that we can’t stop from expanding, Mary Frances wrote yes, mostly about food as a cultural fulcrum, but her body of work includes a screenplay, a children’s book, essays, and more.

Fisher, as far as I can tell, was not one to be contained. She certainly wasn’t interested in being defined by those in power at the time. Her books drew outside the lines a thousand times over. Fisher had her critics (including herself) but she wrote deliberately, with purpose and pleasure, refusing to do what was expected of a 1930s lady. She wrote about food, yes, but really she wrote about life. What it was to be a woman, a mother, a wife. What it was to exist in a world that didn’t often connect the act of eating with pleasure, and certainly not in the pages of Ladies’ Home Journal, McCall’s and the like.

This sort of thing happens single every day, of course; we expect — either by track record or more overt statements — public figures, companies, entities to stay in their lane. In two-week-old tech headlines, loyal users of ChatGPT lost their goddamned minds over an update that creates a chatbot companion who is,

"less effusively agreeable, uses fewer unnecessary emojis, and is more subtle and thoughtful in follow‑ups compared to GPT-4o. It should feel less like 'talking to AI' and more like chatting with a helpful friend with PhD‑level intelligence.”

Chatbot users did not, apparently, appreciate the agreeableness of the upgraded model that functioned outside expected norms. Like the bright shiny new bot, Fisher, too, was never much motivated by what others found agreeable (although she was admittedly not immune to criticism).

Going back to Reichl’s gorgeously rendered verbal portrait of her last meeting with Fisher:

She [Fisher] is slightly flushed, sipping a mysterious pink drink through a straw. Sniffing quietly, I discern the lush herbal scent of gin. She smiles and takes another sip. “Sobriety,” she whispers, “is a rare and dubious virtue. If that at all.”

England had the wild and brainy Elizabeth David, but the American food writers were all good girls, virtuous to a fault, who wrote about keeping house and family cooking. Feeding their families was a job, which is undoubtedly why the best-selling cookbook of the proto-feminist 60s was The I Hate to Cook Book. The notion that a woman might pour herself a glass of wine and cook a meal for the pure pleasure of the act never crossed their minds.

What a thing, to do something for the pure pleasure of it. Or because you believe it will make the world a better place. Or because you can. Whatever it is, a reminder: Do. The. Thing.

As James Wood notes in his seminal work How Fiction Works, the point of a literarily inspired pleasurable pursuit is that it might “educate you in moral complexity and sympathy. It might make you a better ‘noticer of life.’” So too do events that run headlong into your expectations about how one is supposed to be, what one is supposed to do, how one is supposed to act. Assuming are rightfully obsessed with the third season of The Gilded Age4, you will recognize this in the character of Bertha Russell who, after spending years trying to do the exact right thing to secure her exact right place in society, insists on pushing boundaries about who can and cannot (specifically as it relates to divorce) be included in society events, even as her own world begins to fall apart.

Fisher is certainly not alone in her genre experimentation. Anthony Bourdain struck literary gold with Kitchen Confidential, but also tried his hand at crime fiction, Bone in the Throat, and Gone Bamboo, his first two book-length creative jaunts. In foodie circles, former Gourmet Magazine columnist Laurie Colwin is beloved for Home Cooking and More Home Cooking, but the bulk of her work is in the fiction realm. Dwight Garner, a no-holds-barred New York Times literary critic, released a food-centric memoir, The Upstairs Delicatessen, which, for the record, didn’t receive nearly as much attention as I think it should have. And Fisher’s friend Ruth Reichl has, in her post-Gourmet life, taken a go at turning her experience in the food world into fictionalized tales.

I’d be remiss to string you along without a brief review of Fisher’s book, which the August 15, 1947 Kirkus Review calls a

“tale of a wandering wanton, whose character contains no glimmer of human decency […] An odd tale […] M.F.K. Fisher has a unique gift, if one that is sybaritic, ultra-sophisticated, and for that market.”

Alright 1947 reviewer, I see your back-handed compliment, the snide side-eye with which you suggest Mary Frances is uncouth for infusing her work with sensuality, snobbery, sophistication. These are the words of a begrudging admirer, for no matter what you think of a woman who enjoyed the finer pleasures of life without self-conscious apologies, the fact of the matter is Fisher herself had serious doubts about her work.

Hamilton Basso, writing for The New Yorker had little patience for her fictional experiment, bluntly stating, “I think we can dismiss the whole thing.”5

Dear readers, let me say this: do not dismiss the whole thing. While I won’t argue this is the finest book I’ve ever read nor will it make the top twenty cut, I found it a delightful distraction. Maybe it was just the thing to read on an oppressively humid beach, a single plastic cup of rose in hand, tiny sips interrupted by long plunges in an ice bath until the ice melted and I was too hot to even dream of a second serving. Maybe it was the format that resembled a quartet of novellas rather than a coherent single story thread. But I suspect it was the star of the action, the quite unlikable and yet irresistible primary character without whom the narrative would not exist, the truly singular Jennie, that made me a fan.

Jennie is the very definition of a character who draws outside the lines, smashing accepted societal expectations, as she travels from train to city and back again via rail to destinations unclear. She’s not one to look to for a moral code, nor would I advise befriending a person who reacts to a simple inquiry about a train time in this manner:

She let her gray eyes widen arrogantly as she stared up at the girl. How dared anyone accost her simply because she traveled on the same train? The girl was like all the others, slender as grass, no breasts, no hips, fine long legs, a small head set well on her tender bony shoulders, good clothes, shoes wide and short to make her American feet look French. She had too much lipstick on her small mouth, but her eyebrows were not plucked fashionably thin. That takes courage, to be an individual even about an eyebrow when you are eighteen, Jennie thought appreciatively.

“Yes?” she asked.

“But the train’s gone,” the girl said tremulously. It isn’t on the track. The porter told me…”

Jennie smiled. It was because she knew, in a rush, she was grateful to this silly child for being scared for her. Now she was free to be calm, self-posessed, the ruler. Yes, smiled warmly, and then touched the girl’s arm to reassure the two of them.

Jennie is perfectly pleasant, jolted out of her sycophantic navel-gazing self when she has the upper hand. In that, she is, if we are being honest, like so many of us, absorbed in our own personal daily drama while regarding external forces so far as they relate to our own lives. Kindness percolates under the surface, able to come up for air once Jennie is in command, executing control over the situation at hand.

The beauty of the novel, as is evident, is less present via interpersonal relations and more so in scenes where sensuality and pleasure belong. Take this post-coital passage:

He left before dawn. Jennie turned like a cat and found him gone, and then turned again and slept until the mid-morning sun streaked through the tall shutters. She lay flat as a shadow for a few minutes, her flesh over the fine singing bones like a mold made of cream, of satin, of the fumes of a long-gone brandy. She rang for breakfast and then went into the bathroom.

Her tray was ready when she came out, and she looked voluptuously at the large white envelope on it and made herself wait to open it until she had drunk the hot milky coffee, eaten both rolls, both pats of butter, one marked with a plump bee and the other with a cow.

Signing off with a few links (gifted whenever possible) for my dear paid subscribers, including notes on a mega-simple, mega-delicious salad, the nonfiction book I can’t put down, and what’s generating revenue for traditional magazines. If you want in on the fun, all it takes is a quick smash of the subscribe button. See you on the other side!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Four Top to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.